Late one summer, a health camp arrives in a well-off industrial town in Maharashtra. A young mother, Sunita, gets free medical check-ups for her children at a clinic proudly funded by a local company’s CSR program. Hundreds of miles away in a remote tribal village of Jharkhand, another mother, Meera, waits anxiously under a tin roof for a visiting doctor who never comes. No corporation sponsors clinics in her district – it’s not on any company’s radar. This contrast is no anomaly; it illustrates a broader pattern of regional inequality in who benefits from India’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Some communities – often near corporate hubs – see shiny new schools, clinics, and water projects spring up, while others, equally needy, remain overlooked. The geography of CSR in India has produced “hotspots” flush with corporate-funded development and “coldspots” that languish with little or no CSR presence.

Mapping CSR Across India: A National Overview

India was the first country to mandate CSR by law, through Section 135 of the Companies Act, 2013. The law requires large companies to spend at least 2% of their average profit on social development activities. Over the decade since this mandate took effect in 2014, companies have together spent roughly ₹1.27 trillion (₹1.27 lakh crore) on CSR. Annual CSR expenditures have grown from about ₹10,000 crore in 2014-15 to around ₹34,900 crore in recent years, reflecting a 3.5-fold increase in nine years. This money has been channelled into projects ranging from education and healthcare to rural development and environmental sustainability. For instance, education and health alone accounted for nearly half of all CSR spending between 2014 and 2023, indicating corporate India’s focus on these critical sectors. On paper, these figures suggest a substantial corporate contribution to national development. Yet, a closer look at where these funds go reveals a skewed geography – one where certain states and districts reap a disproportionate share of the benefits.

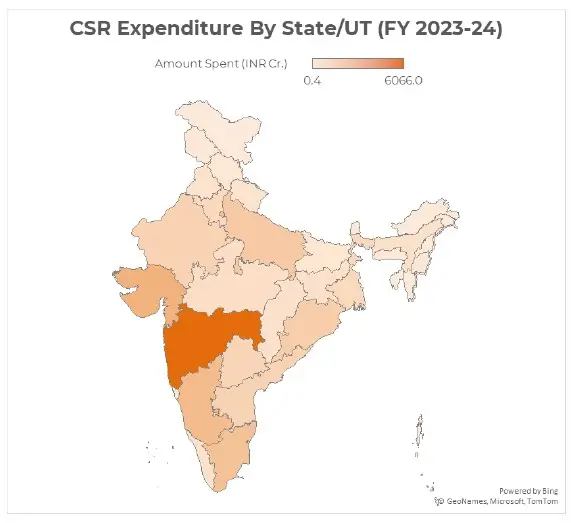

For example, Maharashtra alone received about ₹6066 crore of CSR funds in FY 2023–24, nearly 17% of the national total. In contrast, economically lagging states like Rajasthan, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and those in the North East received only a small fraction of that amount. In short, the national overview of CSR reveals robust overall spending but a lopsided distribution concentrated in a few regions.

CSR Hotspots and Coldspots: Regional Disparities

Multiple studies confirm that India’s CSR funds are heavily concentrated in certain geographies. According to recent analyses, six prosperous states – Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, and the Delhi-NCR region – receive about 60% of India’s CSR funds, while the least developed states (such as those in central and eastern India) receive less than 20%. These stark disparities have led observers to label certain areas “CSR hotspots” , mainly industrialized states and metro areas flush with corporate presence – and others “CSR coldspots”, often rural, poor regions with few or no major companies. Densely

populated but poorer states like Bihar exemplify CSR coldspots: home to millions, it attracts only a sliver of CSR projects in comparison to smaller, richer states. This skew translates into real human consequences – as illustrated by the anecdote of Sunita and Meera at the start.

Why does this geographic bias occur? Institutional and strategic factors embedded in India’s CSR framework drive much of the imbalance. The Companies Act’s CSR rule includes a clause suggesting that companies give preference to the “local area” around their operations. While not an absolute requirement, many firms interpret this as a directive to spend CSR funds near their factories, mines, or headquarters. The result is that corporations often “cluster” their social investments in the states and districts where they already do business. A recent Outlook Business study found that companies disproportionately favor industrialized states – essentially spending “where they are located” – due to this local-area preference and the practical ease of working in familiar territories. In effect, CSR tends to follow the trails of commerce: regions hosting major industries and corporate offices become magnets for CSR spending (the hotspots), while remote rural areas without industry remain left out (the coldspots). This pattern is sometimes described as CSR following a stakeholder-driven model – firms investing in communities that are directly connected to their business and stakeholders, which can double as goodwill and risk management for the company.

Furthermore, there are institutional capacity issues that deter companies from venturing into less developed regions. Companies often struggle to find credible local partner NGOs or to implement projects in districts with weak infrastructure and governance. By law, CSR administrative overheads are capped (often at 5% of CSR spend), which makes it challenging to manage far-flung projects that would require significant on-ground supervision. It is often more feasible for a company to fund an NGO working in a city slum or near an industrial area than to execute a project in a distant tribal block with few reliable partners. These institutional factors reinforce the geographic bias: even well-intentioned firms may shy away from underdeveloped districts due to higher perceived risks, significant efforts from identification to verification to monitoring and implementation hurdles.

There is also an element of strategic choice at play. Some companies follow philanthropic CSR models – through corporate oundations or trusts – that can operate anywhere in the country based on need. Others follow strategic CSR models aligned closely with business strategy and local stakeholder expectations. The latter approach often means prioritizing the company’s immediate communities. For example, a mining company might focus its CSR on building schools and hospitals in the mining belt where its workers and their families live, rather than in a faraway state. This creates positive impacts locally but contributes to nationwide inequality when every firm does the same in its own backyard. As a result, affluent metros and industrial clusters often have an abundance of CSR-funded amenities, while impoverished regions – which arguably need the support most – may see very few such projects. A recent independent report introduced a “Rural Quality of Life” index to compare development needs vs. CSR flows across districts. It found that 70% of districts in India show a misalignment – meaning CSR funding not going where development indicators are worst – and only 30% had a “desirable” match between need and CSR investment. An illustrative case is Balrampur district in Uttar Pradesh: it ranks among the lowest in rural human development in that state, yet over a five-year period it received just ₹6 crore in total CSR funds – averaging a meager ₹23.5 per capita. Balrampur’s experience is sadly typical of many Aspirational Districts (the government’s designation for 115 most underdeveloped districts). Despite policy nudges to channel funds to these areas, only about 2% of total CSR spending from 2014–2022 went to projects in Aspirational Districts, even though these districts house over 15% of India’s population. Clearly, CSR as currently practiced has not served as a strong redistributive tool across regions – it tends to reinforce existing regional disparities.

To address this, some innovative institutional measures are emerging. For instance, the Government of Odisha has developed a dedicated CSR portal (“GO CARE”) that guides corporates to invest in priority development “gap areas” identified by human development indices in the state. By providing district-wise data on needs (health, education, etc.) and matchmaking companies with local projects, such platforms aim to turn coldspots into new CSR frontiers. A few companies and corporate foundations have begun targeting low-HDI regions deliberately, treating CSR as a way to reach underserved communities rather than just those next door. These efforts, however, are still nascent. The prevailing reality is that geography remains destiny when it comes to CSR benefits in India.

CSR vs. Government Welfare: Understanding the Scale

It is crucial to put CSR’s scale in perspective relative to public expenditure. Corporate CSR contributions, though sizable in absolute terms, are dwarfed by government welfare spending. India’s annual private sector CSR spend is a drop in the bucket compared to public development budgets. For example, in FY 2023-24 companies spent about ₹34,908 crore on CSR, while in the same year the central government’s allocation to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA) ballooned to over ₹89,000 crore to support millions of rural households. In other words, one single rural jobs program’s budget was roughly 2.5 times larger than all CSR spending. And MGNREGA is just one scheme – the government’s expenditures on healthcare, education, nutrition, and infrastructure run into lakh crores annually. Similarly, the state of Uttar Pradesh’s annual budget for basic education alone is on the order of ₹50,000 crore, vastly overshadowing whatever a handful of CSR school projects in UP might sum up to.

This comparison drives home an important point: CSR is not a substitute for public investment. Corporate spending is minuscule relative to the development needs of a country the size of India. It can neither fill the vast welfare financing gap nor replace the state’s duty in providing essential services. As one observer bluntly noted, CSR in India is effectively “a post-tax imposition… a devolution of State responsibility onto [private] entities”. Companies simply cannot shoulder the burden of broad public services – nor are they equipped to act as parallel governments in every underdeveloped region. The role of CSR, therefore, must be seen as complementary and strategic, not as an alternative stream of development finance. CSR funds – roughly 0.1% of India’s GDP – are a rounding error next to public expenditure (which is around 15% of GDP on social sectors for the union and states combined).

Yet, because CSR dollars are relatively small and flexible, they can have outsized impact if deployed in a targeted manner. Unlike government budgets (which must cover entire populations and often get thinly spread), CSR projects can concentrate resources on specific communities or innovative pilots. This is where CSR’s value lies: in acting as a strategic lever for hyper-targeted development interventions. For instance, a company might introduce a cutting-edge e-learning program in a few tribal schools, or fund a specialized healthcare initiative for a marginalised group – interventions that are too niche or experimental for

government schemes to focus on initially. Such CSR projects, if successful, can serve as models for the government to scale up or replicate. Many NGOs and policy experts view CSR as risk capital for social innovation. In the best cases, companies have used their CSR to pioneer solutions – such as low-cost rural waste management models, or mobile healthcare vans in remote areas – which governments later adopt on a larger scale. This kind of synergy amplifies the impact of CSR far beyond its modest financial size.

From Gaps to Synergy: Aligning CSR with Development Needs

Going forward, bridging the regional gaps in CSR will require aligning corporate efforts with public development priorities without losing sight of business realities. On one hand, reports like the Transforming Rural India Foundation’s recent study urge that CSR allocations be better realigned with regional deprivation metrics – essentially, nudging ompanies to invest more in India’s neediest districts. On the other hand, CSR must also be strategic for companies to sustain it: it works best when creating “shared value” – benefiting society while also adding value to the business or its stakeholders. Striking this balance is key. Policymakers can incentivize consortia of companies to pool funds for backward areas, perhaps by offering recognition or matching contributions for CSR in Aspirational Districts. State governments can continue developing CSR matchmaking portals (like Odisha’s) to guide corporates towards local needs using data on human development indicators. Within companies, CSR leaders might adopt a portfolio approach: dedicating a portion of spend to “core” communities (local area) and a portion to “extended” communities (high-need areas with no corporate presence). Some public sector enterprises (PSEs) already follow guidelines to direct part of their CSR to priority regions and national causes. This could be broadened to private companies on a voluntary basis.

Ultimately, while CSR will never replace government funding, it can play a catalytic role. It is most effective as a strategic supplement – addressing micro-level gaps, innovating new solutions, and supporting hyper-targeted interventions that government programs may overlook. For example, CSR funds have been used to train tribal youth in digital skills in pockets of Odisha and Jharkhand, or to provide solar lighting in remote hamlets – small-scale projects, but life-changing for those communities. Such targeted interventions, if aligned with broader government schemes (say, skill development missions or rural electrification drives), can accelerate local development in “coldspot” areas. In this way, CSR can help pilot and “crowd-in” development to places that the macro welfare state hasn’t fully reached.

In conclusion, the geography of CSR in India today reflects the country’s economic geography

– concentrated and uneven. High-income states and corporate hubs enjoy a surplus of CSR attention, whereas low-income, high-need regions remain largely neglected by corporate philanthropy. This mismatch underscores that CSR, as currently practiced, is no panacea for regional inequality. Public investment and strong state policy remain the primary engines for

balanced development. However, CSR is not without significance. If reoriented thoughtfully, it can serve as a strategic lever for development, one that works in tandem with public efforts. By leveraging CSR in hyper-targeted ways – funding innovative pilots, reaching niche groups, and filling critical gaps – India can ensure that corporate contributions make a meaningful difference without losing sight of their inherent limitations. The challenge ahead is to turn more of India’s CSR “coldspots” into “hotspots” of progress, not by diverting the entire course of corporate spending, but by intelligently steering a portion of it to where it can matter the most. In doing so, CSR will complement, not substitute, the state – helping to build success stories in human development that are born in boardrooms but realized in the villages and towns that need them the most.

Author: Naman Shandilya